GEORGE (JURRIAEN)

PROBATSKI

The

Immigrant Ancestor

Part I

The Immigrant Ancestor

Part I

By Nora J. Probasco

Copyright © 2009-2024 Nora J. Probasco All Right Reserved

![]()

The first documented Probasco was George (Jurriaen) Probatski, the emigrant ancestor and progenitor of all Probasco families in America. It is estimated he was born between 1615 and 1620, probably in Breslau, Silesia [which is now Wroclaw, Poland], and he died between 1664 and 1665 in Brooklyn, New York. He signed his name George Probatski in a notarial record in June 1654 [Not. Arch. 1329/39v, Gemeente Archief Amsterdam], in which he states he was from Breslau. However, I will use the name Jurriaen, which is the Dutch version of the name George and the name most of his records are listed under. Since we have no early records of Jurriaen before 1643, I think it is important to know some of the history of the areas in which he lived to give you an idea of those events that influenced his native land and would have shaped his perspective.

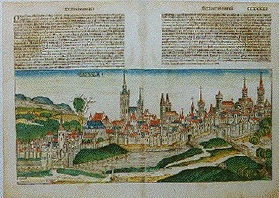

Breslau, Silesia

Silesia was a hub of diversity, the arts and humanities and trade from all parts of Europe. It emerged as a settlement at a convenient crossing on the River Oder/Odra and a junction of major routes leading from the south of Europe to the north, towards the Baltic coast, and from the west to the east, towards the Black Sea. Breslau was the center of that hub. Breslau, the chief Silesian trade center, developed first and foremost because of the trade between Poland and Germany. Throughout history, important trade routes passed through it, connecting the Oder river with the Vistula allowing trade with and between the Netherlands, Germany, England, Bohemia, Russia, Poland and many large and small cities and areas to name a few. It also belonged to the Hanseatic League and was engaged in maritime trade.

Over the years it has gone by many names, Wrotizla in 1013 under Polish rule, then about 1146 it became Wroclaw. In 1241, Mongols invaded Silesia, causing widespread panic and a mass flight of the population. However, Wroclaw held out, and the Mongol commanders passed the city by and resumed their search for Henryk II Pobozny, Duke of Silesia (Henry II, the Pious), a powerful cousin of King Boleslav V of Poland, who was near the Silesian city of Liegnitz with his army. The Mongols continued their invasion until the death of Ogedei Khan (Khakhan), the third son of Genghis Khan and second Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. He was the supreme leader when the Mongol Empire reached its furthest extent west and south during the invasions of Europe and Asia. The Mongols suddenly returned east to participate in the election of a new Grand Kahn. With the Mongols gone, the ruling Silesian leaders decided to rebuild the cities, and introduced the Magdeburg Law in place of the older, customary Slavic and Polish laws to rule the cities. They also made up the recent population loss by inviting new settlers, mostly German and Dutch colonists. Germans, Czechs and Jews settled mostly in the cities, and the Polish still dominated the rural areas. By 1327 Silesia joined Bohemia and its capital city would become known as Vretslav or Wretslaw. Bohemia had grown into one of the leading powers in Europe. Silesia would become a Bohemian province, and Vretslav the second city next to Prague of the kingdom. Silesia would be ruled by them for the next 200 years.

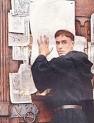

The Protestant Reformation reached Vretslav in 1518 shortly after Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses at the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany on October 31, 1517. Disgusted with the abuses in the Roman Catholic Church of selling "indulgences," Vretslav welcomed the Reformation. Martin Luther's works began to be printed there in 1519 and Protestantism began to spread. Additionally, the Habsburg Monarchy had grown notably at the turn of the sixteen century, from prudent marriages and speculation, its rule included many diverse and distant lands, including Spain, the Netherlands and Austria. In short order, the Habsburgs had become a major power in Europe. Its ruler, Emperor Charles V, a devout Catholic, concerned about invasions from the Turks and the advance of Protestantism, decided to concentrate his energy on his more lucrative Spanish possessions. In 1522 he divided his empire, giving his younger brother, Ferdinand I, the Habsburg lands of Upper and Lower Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and Tyrol. This created the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs which would never again be joined. In 1526, under Ferdinand I, the Hungarian and Bohemian crowns came under the rule of the Austrian Habsburgs, which included Silesia.

Presslaw, as it came to be known, became an active center of the Lutheran Reformation. Though its Roman Catholic diocesan organization remained intact, it was reduced to the role of powerless observer. Rulers changed with the accession of power going to Ferdinand I's son, Maximilian II, in 1564, then to Rudolf II from 1576 to 1612. Interestingly, the Protestant Reformation elevated the status of the German language in Presslaw... until then, Latin was the preferred language of the church and of state administration. The Reformation contributed to a standardized German, in education, the church and literature, replacing regional dialects of German, though the Polish population in Silesia still spoke a dialect called Silsian. Presslaw became the center of German Baroque literature and was home to the First and Second Silesian school of poets. It had excellent primary schools that encouraged the development of the arts and humanities. By the turn of the century, the majority of the population in Silesia was Protestant.

Rudolf II died in 1612 and his brother, Matthias, was crowned emperor. His rule brought in the Counter-Reformation by encouraging Catholic orders to settle in Presslaw. During the Counter-Reformation the intellectual life of the city, shaped by Protestantism and Humanism, flourished, even as the Protestant merchant and middle class lost its role as the patron of the arts to the Catholic orders. Presslaw, even under the rule of the various leaders in the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century including the Habsburgs, was given religious freedom highlighted by the Majestatsbrief (Letter of Majesty) issued in 1609 guaranteeing this freedom. That was until 1617 when Ferdinand II ascended to the throne, promising religious freedom. Once in power, he purposely reneged on this promise, violating the religious freedoms guaranteed by the Letter of Majesty. His reign would signal the start of the Bohemian Revolt and, with it, the Thirty Years War.

Our Jurriaen was born sometime between 1615 and 1620, during this time when the undertones of the Counter-Reformation were setting the flames that would ignite the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) in his native land. In all likelihood, Jurriaen and his parents were Protestant. Silesia, as a largely Protestant territory ruled by the Catholic Habsburgs, was condemned to play an important part in this strife. In the years that Jurriaen lived in Presslaw (Breslau), it was a city in chaos being in an area affected by the Thirty Years War. This war began as a religious civil war between Protestants and Roman Catholics, and soon developed into a devastating struggle for the balance of power in Europe. Presslaw (Breslau), predominantly Protestant, was in the crossroads of many of the invasions of the war. In 1626, the forces of Christian IV and Count Mansfield marched through Silesia en route to Transylvania. The following year, the Saxon Field Marshal Hans Georg von Arnim led a successful advance into the province, causing Silesia to request greater protection from Vienna. With the invasion of these foreigners into Central Europe they also brought with them the plague, decimating the population as well.

We know that Jurriaen was literate, as he signed his name in a 1640 notarial document, an interview with the Dutch West-Indische Compagnie (WIC) in 1643 and in a 1654 notarial document, so he must have attended primary school during this turbulent time. What must have been his thoughts as he was learning? There must have been concern for himself and his family. It would not be an ideal situation for a young boy to grow up, as with each assault on the city or death from plague, he would have seen his childhood slipping further away. He would be forced into early manhood before his time. How was his family affected by this? Did he lose family members? Were they displaced by the invading forces?

In 1632, the Saxon Field Marshal Hans Georg von Arnim again invaded Silesia, bringing with him his new Swedish allies, capturing the cities of Lausitz, Sagan, Glogau and besieging Breslau. Many of the soldiers and mercenaries were under paid or not paid at all, so many resorted to plundering and looting as they marched.

In a recently found 1640 notarial document, we know that George Probatski was in Amsterdam, New Netherlands at that time.

In spite of this, we know from a 1643 WIC document recently found that Jurriaen went to Brazil as a blacksmith, and would have gone through his training during this turbulent time. In Breslau, various trades and crafts fell under the rule of guilds. Specifications of products, pricing and training were decided by these guilds for someone to become a member. Only members could practice their trade in a large city. The smith and/or metal working guilds adopted the apprentice approach to teaching young men the trade.

Young Jurriaen did not let war or plague stop his dreams for the future. At about 15 or so he would have begun his apprenticeship to be a blacksmith. He or his family would have paid a sum of money to a master blacksmith and Jurriaen had to agree to serve him for a fixed period, usually seven years. The master blacksmith, in turn, would have promised to provide him with food, lodging, and clothing, and to teach him the craft. At the end of the seven-year period he would have to pass an examination by the guild. If he was found fit, he would then become a journeyman and worked for daily wages. As soon as he saved up enough money, he could set up a shop of his own and in turn become a master blacksmith, taking in apprentices and journeymen. Full membership in a guild was reached only by degrees.

Guilds were begun in the Middle Ages, however over time, as the guilds “prospered and increased in wealth, they tended to become exclusive organizations. Membership fees were raised so high that few could afford to pay them, while the number of apprentices that a master blacksmith might take was strictly limited. It also became increasingly difficult for journeymen to rise to the station of masters; they often remained wage-earners for life. The mass of workers could no longer participate in the benefits of the guild system.” This is probably what happened when Jurriaen finished his apprenticeship.

In 1642, the Swedes again invaded the area plundering and looting as they marched, leaving cities, towns, villages and farms ravaged. They would maintain a presence in Silesia while their troops invaded other areas. This would last for six years ending with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. It has been estimated that the area around Breslau, Silesia lost between 33% to 66% of its population between 1618 and 1648.

Urban Societies in East-Central Europe

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown: Population Size of Selected Cities, 1500-1650

Breslau-

1500-1530 20,000-25,000

1550-1580 23,500-29,500

1600 30,000-32,000

1640 18,000-25,400

Considering that he may have reached a dead end in his chosen trade, and the aspects of war and plague that would have been all around him, it is not surprising that Jurriaen would choose to leave his home and family in pursuit of a better life for himself. We also do not know how many of his family were lost. If the small amount of results from the search for Jurriaen's DNA haplotype in a large European database are any indication, not many survived.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

The Netherlands had become a refuge for those of the Protestant faith from religious persecution. Its ports were used by many who were not Dutch. The Dutch, at this time, were one of the reigning leaders of shipping and trade in the world, and as was previously discussed, the Netherlands readily shipped through Breslau as did other major European countries and cities because of its convenient location on the Oder River which led to the Baltic Sea and its major trade routes.

The Dutch East (VOC) and West India (WIC) Companies had active trade routes all over the world. Agents of the Dutch VOC and WIC solicited people in the various ports and cities they traded with to settle Brazil with the promise of land, commerce or employment similar to how they colonized New Netherland during the same time. In Brazil, there was plenty of land available for settlement, an active sugar trade and a need for skilled tradesmen. If Jurriaen was stymied in his chosen trade in Breslau as I suspect and possibly dispirited by the constant war and plague, Brazil would have looked like an exciting and adventurous opportunity to a young man.

We do not know if Jurriaen came to Amsterdam to find a better life, or was recruited while in Breslau to work for the WIC in Brazil. More research will need to be done to figure this out and to discover if Jurriaen lived for a time in Amsterdam or just used Amsterdam as a port to go to the Dutch colony of Recife.

There will be a continuation in Part II.

Bibliography

A Companion to German Literature: From 1500 to Present, by Eda Sagarra, Peter Skrine, Wiley-Blackwell, 1999, pp. 203-204

Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, by J. N. Hays, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA, 2005, pp. 97-100

Medieval and Modern History, by Hutton Webster, D. C. Heath & Co., Publishers, Boston, New York, Chicago, 1919, pp. 229-232

Microcosm: Portrait of a Central European City by Norman Davies and Roger Moorhouse, Pimlico/Random House, London, 2002, pp. 151-158

The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and Industry in the Middle Ages, 2nd Edition, Vol. II, M. M. Postan and E. Miller, editors, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1987, pp. 539, 547-554

The Encyclopedia of Christianity by Erwin Fahbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley, Jan Milic Lochman, David B. Barret, John Mbiti, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005, p. 527

The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618-1815, 2nd Edition, by Charles W. Ingrao, Cambridge University Press, NY, 2000, pp. 49-50

The History of the Mongol Conquests by J. J. Saunders, University of Pennsylvania Press, PA, 2001 pp. 85-88

The Lutheran Cyclopedia, edited by Henry Eyster Jacobs & John Augustus William Haas, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, NY, 1899. p. 446

Urban Societies in East-Central Europe, by Jaroslav Miller, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008, p. 25

World History at KMLA located at http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/germany/sildemography.html - Demographic History of Silesia

Back to Contents / Jurriaen Probasco Contents / Back to Home Page